Introduction

In the 'root' portion of this FAQ (FAQ #28) I addressed a situation I had discovered concerning the so-called "evidence" against the validity of NLP and the NLP-related techniques.

This "evidence", was based on a number of experimental investigations of a single NLP-related technique (predicate matching), and a single NLP-related concept (preferred representational systems (PRSs)). What clearly was not being investigated was NLP itself. Which was interesting, given the number of reports whose authors clearly thought that "NLP", eye movements and PRSs were synonymous. That is to say, the basic argument being put forward by academic critics seemed to be nothing more profound than: If we can't find evidence which supports the claims about predicate matching and/or PRSs, then that puts paid to the whole of "NLP".

(Note: Having said that, none of the researchers seemed to realise that "NLP" is a modelling technique and nothing else; or that there was anything to "NLP" other than eye accessing cues, preferred representational systems and predicate matching).

Thus, in his first review, Sharpley commented:

Empathy has been referred to by many authors as one of the primary ingredients of effective counseling (e.g., Ivey & Simek-Downing, 1980; Rogers, 1957) and if NLP [sic] is suggesting that counselors who demonstrate high levels of reflection and empathy will be more effective than those who do not, then little new is being said. If NLP [sic] seeks to promote empathetic responses from counselors, then scales designed to measure empathy ought to, and do, show this (e.g., Hammer, 1983). Although this is a worthwhile procedure for counselors, it does not justify NLP [sic] as a separate theoretical position (nor as the "magic" its proponents quote).

(Sharpley, 1984. Page 246.)

Now Bandler and Grinder were indeed emphasising the importance of creating and maintaining rapport (though their definition was based on communicating with the other person's unconscious rather than everyone feeling warm and fuzzy about each other). And in that respect Sharpley was more or less correct in saying that they weren't offering anything new.

But then again, Bandler and Grinder made it abundantly plain that their ideas stemmed from modelling the behaviour of three long-established exemplars from the fields of Gestalt Therapy (Fritz Perls), Family Therapy (Virginia Satir) and clinical psychology/hypnotherapy (Dr. Milton Erickson). Sharpley himself had made this particular point on the first page of his first article (Sharpley, 1984. Page 238).

And if one is drawing on the patterns of behaviour of long-established therapists, surely it stands to reason that one is going to find little, if anything, that is brand spanking new.

Indeed, Bandler and Grinder themselves highlighted the question of "newness":

Another problem is that the field of psychotherapy keeps developing the same things over and over and over again. What Fritz did and what Virginia does has been done before. The concepts that are used in Transactional Analysis (TA) - "redecision" for example - are available in Freud's work.

(Bandler and Grinder, 1978/1979. Page 13.)

What Sharpley missed, possibly because he was so focused on just one technique and one concept, was precisely what Bandler and Grinder were presenting that was indeed "new".

Firstly they were looking to identify precise language and behaviour patterns used by successful communicators. Not just the bland and not particularly helpful observation that "counselors who demonstrate high levels of reflection and empathy will be more effective than those who do not". Which is about as useful as telling me that the top batters (in cricket or baseball) are those who score most frequently! The observation is true, but virtually useless as a guide to acquiring that skill for myself.

What Bandler and Grinder did was model the skills and then codify them in a way that made it possible for other people to acquire those skills. That is why NLP is modelling. But a very specific modelling process that has been used every healthy, able-bodied person in the world - and quite a few who are not so well off in that respect.

An important flaw exhibited by many would-be critics of the field of NLP (FoNLP) is that they simply haven't taken the time to discover what the FoNLP is really all about. Which has led in turn to the existence of many wholly unsubstantiated claims such as this, from Dr. Steve Novella, M.D., an 'academic clinical neurologist' and ardent skeptic:

The last thirty years of research have simply shown that NLP is bunk. ...

In the case of NLP it has failed every test of both its underlying theories and empirical tests of its efficacy. So, in short, NLP does not make sense and it doesn't work."

(Steve Novella, , March 28th, 2007. http://www.theness.com/neurologicablog/?p=228.

Retrieved 5 April, 2010)

Given that Sharpley's first article said that one-third of the experimental results had supported "NLP" claims, one wonders how Novella justifies the claim that "NLP ... has failed every test".

Moreover, although the author doesn't give any references to support his claims, he does, in the body of his blog, mention another blog which, he says, "is a good summary of the scientific reviews of NLP". Since the blog in question is mainly concerned with the reviews (Dr Michael Heap) and Sharpley, plus a number of other articles (mostly dependent on the accuracy of Sharpley's article(s)), and since the only reviews of the research on "NLP" were highly unscientific, this clearly supports the contention that with the exception of Einspruch and Forman (1985), members of the mental health profession have been citing Heap and Sharpley's work for up to 30 years - without making any significant attempts to verify the accuracy of those articles.

It is therefore worth considering the contents of Sharpley's second article (1987) in which he responded to the article by Einspruch and Forman (1985) which criticised his 1984 article, and also addressed a further batch of studies which Einspruch and Forman cited to give a more representative idea of the shortcomings of experimental investigations into NLP and the NLP-related techniques.

*** The Short Version ***

Critic(s):

(at the time of publication)

Dr. Christopher F. Sharpley: Lecturer in Psychology at Monash University and practicing as a Clinical Psychologist in Melbourne.

Critical Material:

Research Findings on Neurolinguistic [sic] Programming: Nonsupportive Data or an Untestable Theory? (1987). Journal of Counseling Psychology. Vol. 34, No. 1. Pages 103-107.

Nature of criticism:

In his second article Sharpley asserts that by reviewing a further 29 studies he will refute criticisms of his original article put forward by Einspruch and Forman (1985), and confirm the conclusions drawn in the 1984 article.

Original/derivative:

Not at all. This time Sharpley's article was fourth in line - behind Dorn et al, Sharpley himself and Einspruch and Forman. And again Sharpley's article was dependent on other people's research, adding nothing of any consequence to what had already been written except another collection of errors due to inadequate research.

Flaw(s):

Despite his claim that he would refute Einspruch and Forman's criticisms, this is a seriously insubstantial article, in which very little space is given to describing the newly presented research (barely one full column), and logical fallacies are employed as supposed proof of the value of Sharpley's claims.

The paper also includes a glaring and fundamental error which, if hadn't happened already, would have completely undermined Sharpley's claim that he understood the elements of "NLP" that he was discussing.

Indeed, the fact that this article was published at all is proof that the peer-review process can end up supporting totally inaccurate material unless everyone concerned is FULLY acquainted with the details of the subject under discussion.

Conclusions:

This article does nothing to support Sharpley's claims to credibility as a commentator on the FoNLP, and adds nothing of any consequence to the "discussion" about the usefulness of NLP and the FoNLP as a whole.

*** End of Short Version ***

*** 'Director's Cut' ***

More Errors

Sharpley starts his second paper by briefly referring back to his first article and at the same time confounding some of the errors in that (1984) review:

Described by its founders as therapeutic magic (Bandler & Grinder, 1975), neurolinguistic [sic] programming (NLP) suggests that the process of effective communication between persons (particularly counselors and clients) can be enhanced by identifying their "preferred representational system" (PRS) and by using this particular communication modality preferred by a client as a method of effectively helping that client to make changes in behaviour. This process has been referred to as predicate matching and is a basic tenet of NLP (Bandler & Grinder, 1976, p.8).

(Sharpley, 1987, page 103)

Even in these few lines (approximately half of the first paragraph) we find enough errors to call the credibility of the whole article into question:

- Sharpley is still touting the erroneous interpretation of the 1976 description of the PRS, though he now includes the book Frogs into Princes in his list of references. That book alone is sufficient to clarify the situation regarding the PRS concept.

- Sharpley still talks about the "predicate matching" technique in terms of communication - yet promptly implies that it is predicate matching itself which is supposed (by the co-creators of NLP) to have a therapeutic effect, i.e. "help [the] client to make changes in behaviour".

- Sharpley correctly refers to "predicate matching" as a process, and then immediately afterwards claims that it is "a basic tenet of NLP [sic]".

Illogical Logic #1

After this opening Sharpley turns his attention to the criticisms made by Einspruch and Forman, in the same peer-reviewed journal, in a such a way as to rope in the first of several logical fallacies that he uses to defend his own views:

If 44 studies (2 of those referenced by Einspruch & Forman were irrelevant because they did not directly assess a principle or procedure from NLP, and 7 more will be referred to below) of a particular procedure do not show any conclusive effects, then either there is great disagreement in the results that have been reported from these studies, or the procedure is not able to be adequately assessed.

(Sharpley, 1987, page 103)

Sharpley makes his point briefly and clearly. So clearly, in fact, that the logical fallacy is immediately obvious to anyone familiar with the subject. And that fallacy is in the "either ...or" proposition.

This is known as a "false dichotomy". Sharpley claims that there are only two alternatives ("if you ain't for us, you're agin' us!") when in fact there is at least one further alternative, and quite possibly more:

The results are in agreement, though wrong, because everyone based their research on much the same wrong information.

Two of the co-creators of NLP - Grinder and Bandler - first explained the PRS conceptin their book The Structure of Magic II (1976). They further clarified, and expanded on their description in Frogs into Princes (the edited transcript of a seminar that took place in March 1978). They had observed that people used sensory predicates to unconsciously indicate which sensory modalities, or "preferred representational system(s)" they were focused on at any given time. They also noticed that people could, and did, shift quite naturally between PRSs according to the context (see Frogs into Princes, page 36).

Most if not all of the researchers in the experiments on PRSs and predicate matching were still testing an erroneous interpretation of the 1976 description in which a person's PRS was more or less fixed and could therefore be determined in advance. Not surprisingly the results were largely negative. But it surely doesn't take a rocket scientist to recognize that any such experiment, whilst its results may be internally consistent, certainly won't invalidate the PRS concept (which, for reasons explained below, I will call the CPRS - the currently or contextually preferred representational system), let alone the whole FoNLP?

But it is in the next section that the article goes right off the rails.

Einspruch and Forman's (1985)

Criticism's of Research

Sharpley's subheading)

We now come to the section of Sharpley's two articles which, if subsequent writers had bothered to do the relevant research, would in my opinion have removed Sharpley's work from the list of "Reliable sources on the subject of NLP" for ever. But that's not how it works, it seems, so instead we have another measure: "If a critic quotes Sharpley's work as reliable information about NLP [sic], the odds are they haven't done their homework".

In order of appearance, the four errors are:

- The "Right-handed" Myth

- The "Eye Movement Diagram" Myth

- The "PRS Identification" Myth

- The "Mechanistic NLP" Myth

The "Right-handed" Myth

In his first article, Sharpley presented us with this statement:

Although proponents of NLP maintain that predicate matching is useful only with right-handed individuals, few of the studies reviewed have stipulated that this was a precondition for subject inclusion.

(Sharpley, 1984, page 247)

Sharpley didn't explain who he meant by "proponents of NLP". Nor does he explain that the initial claim was never made by any of the co-creators of the FoNLP. Only now, in the 1987 article, does Sharpley clarify the situation:

Einspruch and Forman (1985) criticized Gumm, Walker, and Day (1982) for claiming that NLP applies only to right-handed persons. Gumm et al. quoted [sic] this claim from a workshop run by Bandler and Grinder, and whether it is a widely accepted principle of NLP [sic] or not, it demands examination in controlled studies.

(Sharpley, 1987, page 104)

This is an example of what might be called the "OK, so I got it totally wrong, but there's a reason why I'm actually completely in the right" ploy!

In practise there is no record of Bandler or Grinder ever saying any such thing. So whatever value an examination of the idea might have, it clearly cannot contribute to the results of a study of whether the claims made by Bandler and Grinder are supported by the evidence.

One also wonders why Sharpley was so keen to hang on to the results of this study anyway. Is he admitting that he had no idea that the claim was spurious until Einspruch and Forman raised the matter? Or did he know all along, but kept the study in his review anyway?

Did Sharpley ask himself why, in this one workshop, Bandler and Grinder would suddenly say something they did not believe, and which was diametrically opposed to various statements they had said and/or written elsewhere? (see Bandler and Grinder, 1978/1979, page 23, for example). As it stands this looks suspiciously like a myth based on the word of just three students out of the dozens who carried out the various experiments being reviewed.

(One possible explanation is that Gumm, Walker and Day were just plain confused about the whole subject. They consistently referred to NLP as "neurolinguistics programming" (plural and no hyphen) and, given the design of their experiment, apparently subscribed to the erroneous belief that a person's PRS could be determined by listening to their use of sensory predicates, and/or by their self-report, and/or by watching their eye movements. It may be, then, that they interpreted the "standard" eye movements chart, which really does apply primarily to right-handed people, as though right-handedness applied to the whole of the FoNLP.)

The "Eye Movement Diagram" Myth

Which leads us neatly into the next error:

(In fact Bandler & Grinder, 1979, presented a diagram for identifying PRS from eye movements. They called this diagram "visual eye accessing cues for a normally organized right-handed persons [p.25]. Additionally they referred [pp. 21-36] to their system of PRS identification as being valid for right-handed persons and [perhaps] reversed for left-handed persons. Gumm et al. may, therefore be seen as having followed Bandler and Grinder's (1979) guidelines by restricting themselves to right-handed subjects and thereby maximizing the likelihood of finding an outcome that was supportive of this NLP principle.)

(Sharpley, 1987, page 104)

This is a clear example of the author overlaying what he was reading with his own interpretation.

Although Sharpley had clearly read the label on the diagram correctly - "Visual eye accessing cues for a normally organized right-handed person" - he appears to have promptly re-interpreted it to mean "Eye positions that indicate the five PRSs - V, A, K. O and G", Sharpley (1987, page 104). After which the error is perpetuated by other "researchers", such as the author of the section of the NRC report by Druckman and Swets (1988. Page 139) which reported the alleged findings of the Subcommittee on Influence on "NLP".

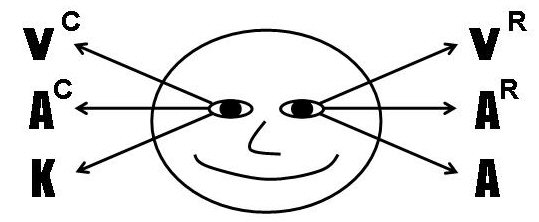

This is particularly inexplicable if we look at the diagram in question (which appears in the NRC report but inexplicably not in Sharpley's articles:

Put very briefly, a person's CPRS is the modality(s) they are paying conscious attention to at any moment. This is indicated by their use of sensory predicates.

The eye accessing cues, on the other hand, indicate which modalities a person is using within a string of accesses which are known in NLP as a "strategy". Not surprisingly, eye movements can sometimes switch very rapidly - literally "in the blink of an eye" - in the course of a single strategy or "train of thought". Which is why it is completely impractical to try to copy the eye movements that accompany someone else's thoughts, or to pick out just one eye movement as an indication of the person's CPRS

As regards the subsequent claim, that the text on pages 21-36 (in Frogs into Princes) is about how to identify someone's PRS, this, too, is totally misguided. In reality that section describes the eye accessing cues. It was unfortunate that, having apparently convinced himself that a PRS could be identified by some's eye movements, Sharpley assumed a connection here which simply didn't exist.

In practice the "standard" eye accessing chart is nothing more than a set of guidelines. The real claim, far from trying to stick people into a few pigeonholes, is that we tend to be fairly consistent in the way our eyes move in accordance with our thoughts, but regardless of whether someone is left-handed, right-handed or ambidextrous, they may not conform to the "standard" positions. Thus this statement from Bandler and Grinder:

You will find people who are organized in odd ways. But even somebody who is organized in a totally different way will be systematic; their eye movements will be systematic for them. Even the person who looks straight up each time they have a feeling and straight down each time they have a picture, will remain consistent within themselves.

(Bandler and Grinder, 1978/1979, page 27)

The main point of having the eye accessing cues chart is not that everyone should follow it to a "t" but that it is a reminder of which positions it is useful to know about. It is then up to the individual NLPer to discover which position any particular person moves their eyes to for each of the cues.

The wary reader will no doubt want to consider the contents of Sharpley's two reviews, and especially his interpretation of the evidence, with these misunderstandings in mind.

The "PRS Identification" Myth

And talking of PRSs:

... in the NLP literature (e.g., Bandler & Grinder, 1976), the presence of the PRS is accepted as a fact and its accurate identification is a primary aspect of effective therapy in which reliable counselor-client predicate matching is assumed to enhance communication.

(Sharpley, 1987, page 104)

There is some truth in this statement, but only some. Responding to another person's CPRSs is one of a number of ways to help communication to flow more easily, which is useful in a therapeutic/counselling context - AND in any other communication.

By clinging to his confusion over how to identify someone's CPRS Sharpley managed to make a simple task look like very hard work.

According to Sharpley, eye movements, self-reporting and listening to verbal predicates were "the three NLP methods of determining the PRS" (Sharpley, 1984. Page 242), though despite all the other references in his his articles, this is one "claim" for which Sharpley did not provide a direct quote - mainly since no such quote existed.

Indeed, as Bandler and Grinder had said, in both 1976 and 1978/1979, and as Hammer had demonstrated in 1983, and as Graunke and Roberts demonstrated in 1985, the one way to determine someone's CPRSs is by "tracking and matching". There is no need to pre-determine someone's PRS by counting predicates, or trying to remember the result so you can match it later on.

All you have to do is notice each of the sensory predicates a person is using as they speak and reflect them back when you next reply.

Surely nothing could be more simple?

The 'Mechanistic NLP' Myth

And finally, in attempting to refute Einspruch and Forman's claim that "graduate students do not represent highly experienced and senior therapists", Sharpley hit back with the excuse that, "the use of such persons is not only traditional in the comparative psychotherapy literature but can also be a strong argument for both the ready application of a specific procedure and the robustness of that procedure" (Sharpley, 1987. Page 104.)

As regards the "tradition" involved, it has also been traditional that a major portion of all psychological research has been carried out on American college/university students - no matter how unrepresentative they may be of the general public, in the US or anywhere else. Indeed, Sharpley himself quite rightly raised this very point in his first article (Sharpley, 1984. Page 247).

Moreover the plea that "this must be an OK way to do things, because this is how we've always done it" really doesn't hold enough water for a gnat to bathe in. What Sharpley seems to be proposing here is some kind of "psychotherapy by the numbers", and that the technique under discussion - predicate matching - should be purely mechanistic. In effect, regardless of all other factors:

- You use a sensory predicate

- I respond (always with the same pre-determined predicate), and

- Shazam! We have rapport.

This is another strange claim to make, given that at the time that he wrote his first review, as well as fulfilling his academic duties, Sharpley was, in his own words "practicing as a Clinical Psychologist in Melbourne".

- Would Sharpley, wearing his clinical psychologist's hat, reflect clients' predicates in a way that made it seem like a chore? Or so clumsily that it was obvious to the client what was going on?

- Did he carry out his own work with a book of instructions at hand, or in his head, which told him "When the client does A the therapist must always do B"?

- Did he think the student counsellors in the Dowd & Hingst (1983) study were adequately trained given that the experimenters felt it necessary to monitor their behaviour and direct them via "bug-in-the-ear devices during interviews to ensure that they maintained their correct treatments"?

And what of Sharpley's subsequent observation on the situation:

If it is the case that NLP [sic] can be demonstrated as effective only by those who have undergone the "extensive training" that Einspruch & Forman (1985, p. 594) referred to as necessary for effective use of NLP [sic], then NLP [sic] may well be a successful (if elusive) procedure.

(Sharpley, 1987, page 104)

Notice that "NLP" is referred to here as "a ... procedure". Which seems to indicate that Sharpley thinks that "NLP" and predicate matching are synonymous. Moreover, since this sentence is immediately followed by the phrase "On the other hand" I think it is reasonable to assume that Sharpley is not entirely convinced that this predicate matching is likely to be of much use. So let's apply this thinking to the work of a clinical psychologist:

- Are there techniques used in clinical psychology that a graduate student could learn quickly and easily? Yes.

- Does this mean that a graduate student, having learnt the basic format of any technique, can immediately go out and apply that technique with the same degree of skill as an experienced practitioner, such as Dr. Sharpley?

In which case why is it necessary to go on a university courses as a preparation for a career in therapy? We could just hand out manuals containing the basic instructions for a collection of core techniques; make sure our would-be therapists can read and understood the instructions, and then hand them a certificate and a license to practice

- Dr Sharpley argues that "one need only cursorily read the literature to discover many successful applications of therapeutic procedures by graduate students" (Sharpley, 1987, page 104). Unfortunately he provides neither examples nor reference to support this claim, so we have no way of telling how widely this generalization can be applied, nor whether the observation is applicable to something like the FoNLP.

- We might also consider rather less optimistic, but possibly more realistic, observations such as this, from Dr Steven Novella, a clinical neurologist at the Yale University Medical School:

[There is] an endemic problem within the mental health field. Part of the problem is that the field is very broad, with multiple parallel professions, including psychiatry, clinical psychology, social work, and counseling. Also within each profession there are multiple theories and traditions, many mutually exclusive ... although there is a great deal of legitimate science within the mental health field, in practice it is rife with pseudoscience and nonsense."

(Novella, 2007)

Further Research

This section starts with some rather unsubtle number juggling. In his 1984 article Sharpley reported that, over the 15 studies (some of which involved testing multiple hypotheses), the 29 results included 17 non-supportive results, 3 uncertain, and 9 supportive, hastening to point out that 9 is "less than one third" of 29 (sure is - only 31% as compared to 33.3%).

In this second paper, for reasons best known to himself, Sharpley revises the figures in the first article so as to base them on the number of studies (15) instead of the number of results (29) (Sharpley, 1987. Page 104). So they now read "2 were supportive, 5 were uncertain or mixed results, and 8 included data not supportive of the principle that they [allegedly] investigated". Despite the strange wording Sharpley presumably viewed this version of the figures as being a far more accurate result. After all, using this new approach, any supportive result that appears in the same study as an unsupportive or inconclusive result is automatically lost as the entire study becomes an "uncertain or mixed result". Using this simple trick changes those 31% supportive results into just 13.6%! Bit of a no-brainer, really.

Next, having taken an entire eleven page article to deal with his first fifteen studies, Sharpley now manages to cram his review of a further 23 new studies (and one from the original 15) into just one column (including subheading). The descriptions are, to say the least, brief, and often overlook important details.

Thus, for example, we are told that: "Rebstock (1980) found no significant relation between predicate matching and positive evaluation of counselors by clients". What we aren't told is that Rebstock actually "recommended that further research on matching techniques in relation to rapport be conducted, since the present study demonstrated the lack of effectiveness of a particular training design, not necessarily the lack of effectiveness of matching techniques in general" (Rebstock, 1980. Abstract).

Sharpley also refers to "22 studies that were identified by Einspruch and Forman (1985) [which] showed that the breakdown was 3 supportive, 4 uncertain, and 15 non-supportive."

I'm a little confused here, since I found 23 new studies in this section, with a breakdown of: 17 non-supportive, 3 supportive, and 3 which, despite the researchers' claims, seemed to have only the flimsiest connection, if any, with NLP-related concepts or techniques. Having said that, however, as many as 20 of the studies were actually useless, for various reasons.

By and large, the reasons were the same as those seen in the earlier review - using a seriously inaccurate definition of the preferred representational systems (PRS) concept, using an inaccurate description of how a person's PRS could be determined, and so on. Indeed, some researchers seemed to have simply invented their own claims and then attributed them to "NLP".

- Appel (1983) claimed that he had "measur[ed] the relationship between attraction and the respondent's primary, secondary and least-used representational systems (used the inaccurate definition).

- Fromme and Daniell ran an experiment that involved "examining intercorrelations among response times ... for extracting visual, auditory, and kinesthetic information from alphabetic images (nothing to do with any genuine claim).

- Margaret Green decided that if predicate matching worked then it should create "trust" - which Green "operationally defined as self-disclosure". Green assumed that since the subjects didn't do what she thought they ought to be doing, regardless of whether Bandler and Grinder's claims substantiated her theory (they didn't), then obviously it must be Bandler and Grinder's ideas which were at fault ("observer effect").

- And so, and so on.

Sharpley's article makes no mention of such problems.

Overview of Research Studies

In this section, though it may seem, by now, hard to believe, Sharpley presents even more convincing evidence that his two articles are based on a profound misunderstanding of the relevant aspects of the authentic FoNLP, and of rational investigations in general.

After reminding us that his latest findings involve some 44 studies, Sharpley quotes from one of the studies conducted by Fred J. Dorn, thus:

"In order for counselors to respond effectively to clients in their PRS, it is important that the PRS be accurately assessed" (p. 154).

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 105)

He then goes on to say:

Data collected in 44 studies clearly indicated an overwhelming finding that (a) the PRS cannot be reliably assessed; (b) when it is assessed, the PRS is not consistent over time ...

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 105)

Now Sharpley included two books by Bandler and Grinder (The Structure of Magic II (1976), and Frogs into Princes (1978/1979) in his list of references for the 1987 article, and The Structure of Magic II in the 1984 list. So how do we square his point (a), in the last quote, with these statements:

'In order to identify which of the representational systems is the client's most highly valued one (i.e. the client's PRS), the therapist needs only to pay attention to the predicates the client uses to describe his experience.'

(The Structure of Magic II, 1976, page 9)

'The "representational system" is what's in consciousness, indicated by predicates.'

(Frogs into Princes, 1978/1979, page 28)

It's that simple.

As was said earlier, you listen to the other person's predicate usage and you reflect it back. We can argue about whether the technique works, but there is no rational basis for the claim that "the PRS cannot be reliably assessed".

Likewise, on the point of consistency, Sharpley's observation is true, but since the definition takes account of this it is difficult to know why Sharpley is still flogging this particular equine carcass some ten years later.

And Sharpley has some more surprises up his sleeve before this section closes.

Illogical Logic #2

After another brief bout of juggling with statistics, which is accompanied by a little chart showing that only 13.6% of the 44 studies supported what Sharpley and the researchers seemed to think were authoritative claims made for "NLP", we are told that:

It is very difficult to accept (as Einspruch and Forman, 1985, suggested) that all of these researchers were guilty of the "methodological errors" (p. 590) that they claimed leave the total research on NLP [sic] to date inconclusive and "trivial" (p. 594).

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 105)

But just a minute, is that phrase "it is difficult to accept" a genuinely scientific measure? In a word, "no". It is another "logical fallacy" - an "argument from personal belief"? To put it bluntly, whether Sharpley himself can or cannot believe something is neither here nor there. Nor does repeating the argument - in the next column - increase its effectiveness:

The basic tenets [sic] of NLP [sic] have failed to be reliably verified [sic] in almost 86% of the controlled [sic] studies*, and it is difficult to accept that none of these 38 studies (i.e. those with nonsupportive, partial or mixed results) were performed by persons with a satisfactory understanding of NLP (or at least enough of a satisfactory understanding to perform the various procedures that were evaluated).

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 105)

(* It is unclear what "controlled studies" Sharpley is referring to, here. In his previous article he commented that:

A series of controlled studies using reliable indicators of change in clients' behavior (rather than their perceptions of counselors, which may not be correlated with problem dissolution by clients) is called for.

(Sharpley, 1984. Page 247. Italics added for emphasis)

But why would one need to call for "a series of controlled studies" if the existing studies had all included an adequate control group?)

It is also worth noting that there is no mention, in either of Sharpley's articles, of the "observer effect" - the possibility that researchers may tend influence the results of their research, even when they mean to be scrupulously unbiased.

The 44 studies under consideration were carried out across a span of approximately 9 years, 1977-1985 inclusive. And we have direct evidence that at least some of the experimenters knew about other studies on the same subject. Not least because some researchers had more than one bite of the "apple":

- Dowd published reports on two studies (1982, 1983), albeit with two different co-reseachers

- Graunke wrote his dissertation (U. of Houston, 1984) the year before he co-authored the article (1985) featured in Sharpley's second review

- Fred Dorn, with and without associates, published four articles, all in 1983, one of which was a review of the literature on research into "NLP" (though the review article wasn't included in Sharpley's references).

There is also evidence within some of the reports that the authors were aware of similar research, such as:

- Dowd & Hingst (1983): "Results were compared with previous research"

- Elich, Thompson & Miller (1985): "Data are discussed in the context of an ever-growing literature that does not support Bandler and Grinder's model"

- Graunke (1984): "Past research and publications of NLP have almost exclusively considered predicates as a trait characteristic"

- Graunke & Roberts (1985): "Findings were incongruent with R. Bandler and J. Grinder's (1979) conceptualization ... but they support A. Hammer's [1983] recommendations"

(Note that Graunke fails to understand that the results gained by Hammer and his own study actually confirm what "R. Bandler and J. Grinder" really said in the seminar transcribed as Frogs into Princes (1979).)

It is entirely appropriate, of course, for researchers to inspect the literature relevant to their own work. Which is why it makes no sense at all to imply that the studies represent independent views on the subject being researched. In practice many articles and dissertations - including Sharpley's own reviews - erroneously refer to PRSs and predicate matching as though they were effectively all there was to "NLP". Which may itself be prima facie evidence that at least some of the researchers were piggy-backing on previous studies rather than going back to the source and reading the original material they were allegedly investigating.

I am reminded of the joke about the tourists, lost deep in the English countryside, who asked a passing yokel how to get to Arminster, the town where they had planned to stay the night.

"Get to Arminster?" the yokel repeated, rubbing his chin thoughtfully. "That in't very likely, souls. If you want to get to Arminster, you'd best not start from 'ere!"

Referring back to an earlier point, even an entirely adequate control group can't save the day if the experiments are themselves invalid, and regardless of Sharpley's beliefs, the experimenters did indeed get it wrong. Not, in most cases, because they couldn't carry out the procedures, but because they were carrying out the wrong procedures. That is to say, they were carrying out procedures based on misinterpretations of the 1976 definition rather than the fuller 1978 description. Only two of the researchers were (possibly) working before 1978, and they both invented their own errors - Owens (1977) by assuming that there were three ways of detecting a person's PRS, and Shaw (1977), who presented predicates to his subjects instead of having them produce the predicates.

Since Sharpley himself seems to have shared almost every misconception presented by the researchers, along with a desire to substantiate his own very negative views of "NLP", this "not acceptable" plea is clearly very much out of place in what is apparently being offered as an unbiased review of the subject being investigated.

Value of NLP: Implications From Research Findings

for Counseling Practice

(Sharpley's subheading)

In this final section Sharpley seems to become somewhat equivocal in his views on "NLP".

The section starts with a repeat of the previous pattern of quoting flawed statistics and then using them to justify a conclusion:

In the opening section of this article, it was suggested that the outcome data on NLP [sic] might show (a) a lack of conclusive effects or (b) the essential untestableness of NLP [sic]. Because only 13.6% of the 44 studies reviewed supported NLP [sic], one may exclude the first alternative. There are conclusive data from the research on NLP [sic], and the conclusion is that the principles and procedures suggested by NLP [sic] have failed to be supported by those data.

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 105)

To adequately explore this multi-part, interlocking claim we need to break it down into its constituent parts:

- In the first sentence Sharpley "primes" us by setting up another "false dilemma" - - the outcome data can only mean (a) or (b). Now that could be correct, but Sharpley certainly hasn't substantiated his claim.

- Next he quotes a statistic which is, on the face of it, correct, but which actually rests on not one but two false assumptions:

- It assumes that "NLP" consists of little more than the PRS concept and the predicate matching technique, and

- It assumes that the 44 studies accurately addressed genuine claims made about the authentic definitions of the PRS concept and the predicate matching technique.

- It assumes that "NLP" consists of little more than the PRS concept and the predicate matching technique, and

In fact, however, we have seen that neither of those assumptions is justified.

- Neither Sharpley nor any of the researchers ever identify the true definition of NLP - the modelling process; and there is certainly a lot more to the FoNLP as a whole than one concept and one process.

- Likewise, both Sharpley and the researchers have made fundamental errors in their interpretation of the details of both of the items they are allegedly investigating. Thus it is completely misleading for Sharpley to imply that the 44 studies have produced uniformly valid data about any aspect of the FoNLP.

At this point the article takes a very new turn:

On the other hand, Einspruch and Forman (1985) implied that NLP [sic] is far more complex than presumed by researchers, and thus, the data are not true evaluations of NLP [sic]. Perhaps this is so, and perhaps NLP principles are not amenable to research evaluation. This does not necessarily reduce NLP [sic] to worthlessness for counseling practice. Rather it puts NLP [sic] in the same category as psychoanalysis, that is, with principles not easily demonstrated in laboratory settings but, nevertheless, strongly supported by clinicians in the field.

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 105)

Another interesting play on words here, and another failure to get to grips with the subject the author apparently thinks he is addressing.

Why does he say, "this does not necessarily reduce NLP [sic] to worthlessness to counselors" (italics added for emphasis) when he has already conceded, in his first article, that:

If NLP [sic] seeks to promote empathetic responses from counselors, then scales designed to measure empathy ought to, and do, show this (e.g., Hammer, 1983).

(Sharpley, 1984. Page 246)

Anyway, Sharpley continues:

Not every therapy has to undergo the rigorous testing that is characteristic of the more behavioral approaches to counseling to be of use to the therapeutic community, but failure to produce data that support a particular theory from controlled studies does relegate that theory to questionable status in terms of professional accountability.

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 105)

Make of that what you will.

One minute it's OK to not have gone "rigorous testing", and the next, if you haven't carried out controlled studies which support your theory then you don't get "professional" approval.

(In this context, "professional" refers to academic psychologists and the like who, for thirty years, have uncritically recycled Sharpley's two profoundly flawed studies as though they were based on genuine, accurate knowledge of the subject. Make what you will of that, too.)

But this ambiguous attitude has not yet run its course. Straight after relegating "NLP" to the back benches, Sharpley writes:

What is it then that NLP [sic] can offer the practitioner? First, the process of predicate matching to enhance support is worthwhile, and there is a great deal of literature on counselor mirroring that supports the practice of counselors' using verbal (and nonverbal) behaviors similar to their clients'. This procedure induces empathy, and although this is of great value for effective counseling, this can hardly be claimed as a discovery first made in NLP [sic].

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 105-106)

Just two points need to be made here:

- Although Drs. Heap and Sharpley still imagine (when I corresponded with them online, in 2008 and 2009 respectively) that "NLP" is some kind of therapy, they are both mistaken.

NLP is a modelling process and nothing else. Amongst the related techniques a mere handful - the "fast phobia cure", for example - are clearly therapeutic, but all the rest are about enhancing communication skills in any context

- On the first page of his first review (1984), Sharpley specifically mentions that Bandler and Grinder, 'based their observations on "therapeutic wizards" ... such as Satir, Erickson, and Perls.' (page 238).

Why, then, does Sharpley now make the point that some comment 'can hardly be claimed as a discovery first made in NLP [sic]'? Given Bandler and Grinder's openness about how they collected the original material by modelling people who already were already using the techniques, why on earth would either of them ever make such a claim? The "newness" was in what the co-creators did with the information.

The next observation is equally unfathomable:

Second, assisting clients in moving from one sensory modality to another (e.g., visual-auditory-kinesthetic) to aid in understanding an issue has long been used by Gestalt therapists; this is not an NLP {sic] invention either.

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 106)

Correct. But had Sharpley really forgotten that quote from his first article - the one that mentioned Fritz "Gestalt Therapy" Perls as being one of the people who were "observed" by Bandler and Grinder? Again the implication that "NLP" is somehow at fault because some part of it can also be found elsewhere seems to be as futile as a down-market newspaper trying to pump up its circulation by running an expose on "British Queen Married to Greek Prince"!

The author continues in this strain for several sentences, apparently struggling to find something telling to comment on, but finding nothing. What we get instead are some very strange nuggets:

... the process of reframing, or "positive asset search" [sic], has been noted in at least five major therapies besides NLP

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 106.)

"Reframing" is relevant. But if Sharpley thinks that the NLP-related "reframing" techniques are the same thing as "positive asset search", that's just another example of misunderstanding what the FoNLP is really about.

Even predicate matching itself can be effectively accomplished by using ongoing counselor responses to client statements (e.g., Hammer, 1983) without invoking the concept of the PRS or its identification

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 106.)

Which is as clear a statement as one could find that Sharpley has no idea that the words the counselor responds to ARE the client's PRS indicators!

There are other procedures that NLP suggests [sic] are beneficial to counseling (e.g., anchoring, changing history) but that are not specific to NLP.

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 106.)

What on earth is going on here? If Sharpley understands that "NLP" is more than just PRSs and predicate matching, why does he leave it until so near the end of his second article to mention the fact? And now he has mentioned it, why is the information presented so briefly?

Did Sharpley have this information all along, without recognizing its significance?

We've already dealt with the allegation that "NLP" was being presented as something new.

(* As for the second allegation, given the number of times he made mention of words such as "magic" and "wizards" in Bandler and Grinder's books The Structure of Magic I and II, and the references to Erickson, Satir and Perls as "wizards", etc. - it would seem that Sharpley was somewhat irritated by the use of such words in relation to what was also one of his own spheres of activity, as a clinical psychologist.

So for Dr Sharpley, and anyone else who finds such stuff decidedly "woo woo", an explanation is offered in the side bar alongside this paragraph.

The author now returns to his old stomping ground:

... although the proponents of NLP claim its underlying principles (e.g., the existence of the PRS, methods of identifying the PRS, and predicate matching as a necessary condition for effective therapy) to be true, they have little to support them and much to answer in the research literature.

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 106.)

But hold on a moment. In one place something is described as a "basic tenet", somewhere else it is a "process", and now it is a "principle". That "tenet" and "principle" are related is tenable. Trying to tie either of them into "process" isn't.

Even less credible is the allegation that the co-creators had said that "identifying the PRS, and predicate matching as a necessary condition for effective therapy". Especially since Sharpley had already been corrected on this specific point by Einspruch and Forman in their response to his first article:

Nowhere do Bandler and Grinder suggest that matching the client's PRS is the key to effective counseling, as Sharpley states, but rather they indicate that it is an important element in effective communication and should be used in conjunction with other techniques.

(Einspruch and Forman, 1985. Page 590. Italics added for emphasis)

And the Druckman and Swets report of 1988 includes the statement that:

Sharpley does, however, concede that:

If ... NLP [sic] is presented as a "theory-less" set of procedures gathered from many other approaches to counseling, then it may serve a reference role for therapists who wish to supplement their counseling practice by what may be novel techniques for them.

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 106)

Some readers may think this is a rather sanctimonious expression of what would have been very generous offer, were it not for the fact that Sharpley had played a major role in the misrepresentation of NLP and the FoNLP in the first place.

It certainly does nothing to encourage a belief that Sharpley's reviews even touched on the nature, use, methods, etc. of the authentic FoNLP.

Conclusion

In order to get the full measure of these two articles (Sharpley, 198 & 1987) we could do worse than consider his final paragraph and see how little it actually says of any consequence.

One may conclude that there is little use to the field of counseling research in further replications of previous studies of the principles underlying NLP [sic].

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 106)

Given that all of those previous studies failed to take into account any genuine claims made by the co-creators this seems like a rather counter-productive course of action.

In 44 studies of these principles [sic], they have been shown to be without general support from the data.

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 106)

But then again, why would it be otherwise when the data was derived from seriously flawed experiments?

Future research that can contribute new data on this issue via methodological advances or consideration of different aspects of NLP {sic] may be justified ....

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 106)

Or by researchers starting out with an accurate knowledge of the claims made by Bandler and Grinder rather than launching into woo woo speculations? Wouldn't that be useful?

... but perhaps of more relevance (and value) now would be a careful meta-analysis of the large amount of data already gathered.

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 106)

It is of more "relevance (and value)" to do a meta-analysis of a collection of profoundly flawed research projects than to just check whether anyone had got their basic facts right? Didn't Sharpley himself, and Heap, do some kind of meta-analysis? Did this do anything but further confuse the issue?

Elich et al. (1985) referred to NLP [sic] as a psychological fad, and they may well have been correct.

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 106)

That was a quarter of a century ago, of course.

But then again, Elich et al were the researchers who invented the story that Bandler and Grinder had claimed "that eye movement direction and spoken predicates are indicative of sensory modality of imagery" (wrong). They were also three of the many researchers who hadn't studied the basic resource material with enough care to know that a person's CPRS was flexible, and could not be reliably checked by self-report. Indeed, at the end of their abstract they note that:

Data are discussed in the context of an ever-growing literature that does not support Bandler and Grinder's model and in the context of the difficulties in interpreting the model itself.

(Elich, Thompson and Miller, 1985. Abstract)

Which looks uncomfortably like an admission that the three men knew that they didn't really know what they were doing, but went ahead and did it anyway.

And finally:

Certainly research data do not support the rather extreme claims that proponents of NLP have made as to the validity of its principles or the novelty of its procedures.

(Sharpley, 1987. Page 106)

Emotive, but still wrong.

- Who are these proponents? . Why aren't they properly cited? And if they aren't Bandler and/or Grinder - the only genuine authorities on NLP and the FoNLP - then why are they mentioned at all?

- What, precisely, are these "extreme claims"? In whose opinion, and by what standards are they "extreme"?

- Which experiments, precisely, addressed these "extreme claims", and why weren't they identified as such in the two articles?

- Alternatively, if these two articles don't deal with any studies of "extreme claims", isn't it self-evident that there won't be any data related to them, pro or con?

- What is meant by the reference to the "principles" of NLP [sic]? We have seen already that none of the "principles" mentioned in the previous paragraph actually fit that description.

- Where did Bandler and/or Grinder ever claim that the material they had modelled from various therapists was "novel" or new? This looks like nothing more than one more fantasy motivated by a desire to bring down whatever it was Sharpley thought of as "NLP".

What a pity the author didn't do some careful research of his own before he donned his armour and with the light of battle in his eye, sallied forth to embark upon deeds of derrynge do.

In short, despite all the attention paid to this article (and its predecessor), it turns out to be an example of nothing but inadequate research and unsupported opinions, from start to finish.

References

Appel, P. R. (1983). Matching of representational systems and interpersonal attraction. Dissertation Abstracts International 43(9). United States International University.

Bandler, R. and Grinder, J. (1978/1979). Frogs into Princes. Real PeoplePress, Moab, Utah.

Bandler, R. and Grinder, J. (1975). The Structure of Magic I. Science and Behavior Books, Inc., Palo Alto, California.

Dorn, F. J. (1983). The effects of counselor-client predicate use in counselor attractiveness. American Mental Health Counselor's Association Journal. Vol. 5, No. 1, pages 22-30.

Dorn, F. J.; Atwater, M.; Jereb, R. and Russell, R. (1983). Determining the reliability of the NLP eye movement procedure. American Mental Health Counselor's Association Journal. Vol. 5, No. 3, pages 105-110.

Dorn, F. J.; Brunson, B. I. and Atwater, M. (1983). Assessment of primary representational systems with neurolinguistic programming [sic]. American Mental Health Counselor's Association Journal. Vol. 5, No. 4, pages 161-168.

Dorn, F. J. (1983) Assessing primary representational system (PRS) preference for Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) using three methods. Counselor Education and Supervision, Vol. 23, No. 2, pages 149-156. December 1983.

Dowd,T.,&Hingst,A. (1983). Matching therapists' predicates: An in vivo test of effectiveness. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 57, 207-210.

Dowd, T., & Pety, J. (1982). Effect of counselor predicate matching on perceived social influence and client satisfaction. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 29, 206-209.

Einspruch, E. L. and Forman, B. D. (1985). Observations concerning research literature on Neurolinguistic [sic] Programming. Journal of Counseling Psychology, Vol. 32, No. 4, pages 589-596.

Elich, M.; Thompson, R.W. and Miller, L. (1985). Mental imagery as revealed by eye movements and spoken predicates: a test of Neurolinguistic [sic] Programming. Journal of Counseling Psychology, Vol. 32, No. 4, pages 622-625.

Fowles, J. The Magus (1965). Jonathan Cape, London.

Fromme, D. K. and Daniell, J. (1984). Neurolinguistic [sic] Programming examined: imagery, sensory mode, and communication.. Journal of Counseling Psychology, Vol. 31, No. 3, pages 387-390.

Graunke, B. (1984). An evaluation of Neurolinguistic Programming [sic] : The impact of varied imagery tasks upon sensory predicates. Dissertation Abstracts International 46(6). University of Houston.

Graunke, B. and Robrerts, T. K. (1985). Neuro-linguistic programming [sic] examined: The impact of imagery tasks on sensory predicate usage. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 32, 525-530.

Green, M. A. (1979). Trust as affected by representational system predicates. Dissertation Abstracts International 41(8). Ball State University.

Grinder, J. and Bandler, R. The Structure of Magic II (1976). Science and Behavior Books, Inc., Palo Alto, California.

Hammer, A. (1983). Matching perceptual predicates: Effect on perceived empathy in a counseling analogue. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30, 172-179.

Novella, Steven, Neurolinguistic Programming and other Nonsense. Published on the author's Neurologica blog, on March 28, 2007.

Retrieved from http://www.theness.com/neurologicablog/?p=228, January, 2010.

Owens, L. (1977). An investigation of eye movements and representational systems. Doctoral dissertation 38(10) Ball State University, 1977.

Rebstock, M. E. (1980). The effects of training in matching techniques on the development of rapport between client and counselor during initial counseling interview. Dissertation Abstracts International 41(3) University of Missouri, Kansas City.

Sharpley, Christopher (1984). Predicate Matching in NLP: A Review of Research on the Preferred Representational System. Journal of Counseling Psychology. Vol. 31, No. 2. Pages 238-248.

Sharpley, Christopher (1987). Research Findings on Neurolinguistic [sic] Programming: Nonsupportive Data or an Untestable Theory?. Journal of Counseling Psychology. Vol. 34, No. 1. Pages 103-107.

Shaw, D. (1978). Recall as effected by the interaction of presentation representational system and primary representational system. Doctoral dissertation, Ball State University, 1977). Dissertation Abstracts International

Andy Bradbury can be contacted at: bradburyac@hotmail.com